Hello and welcome to the 56th issue of Place! We all have that house we go back to in our minds. The one that is thick with memories, that anchored our childhood, or served as the launch-pad to adulthood. We can remember its corners, the sounds that surrounded it, echoing in from the street or the wilderness. In this week’s dispatch, Nikole Wintermeier delves into one such home – her family's house in Annecy, France – and the growing pains she went through leaving it behind.

ICYMI! We recently honoured our first birthday by launching a brand new pitch guide because we really want to hear your stories! And the great news is, we can now pay our contributors thanks to our generous subscribers who have supported us through our membership program. We already have a couple pieces coming up that we are super excited to share with you all, and can’t wait for what’s to come.

At Place, we believe that the experiences, sensations and conversations we have as we move about the world stay with us, stacking up as the years go by, forming who we are and the way we view the world. Do you have a letter to share? Send it to us at placeletter@protonmail.com. If you are interested in writing for Place you can find our pitch guide here. If you’re the social type, follow us on Twitter (@place_letter) where you can share your favourite pieces and Instagram (@placenewsletter) for a visual feast. Yours, The Place editorial team.

We gave up our house in Annecy, France a few months ago. But I’m not sure who gave up on who first: did we give up by visiting less and less? Or did the house heave a final sigh of surrender through its crackling ceilings and faulty pipes?

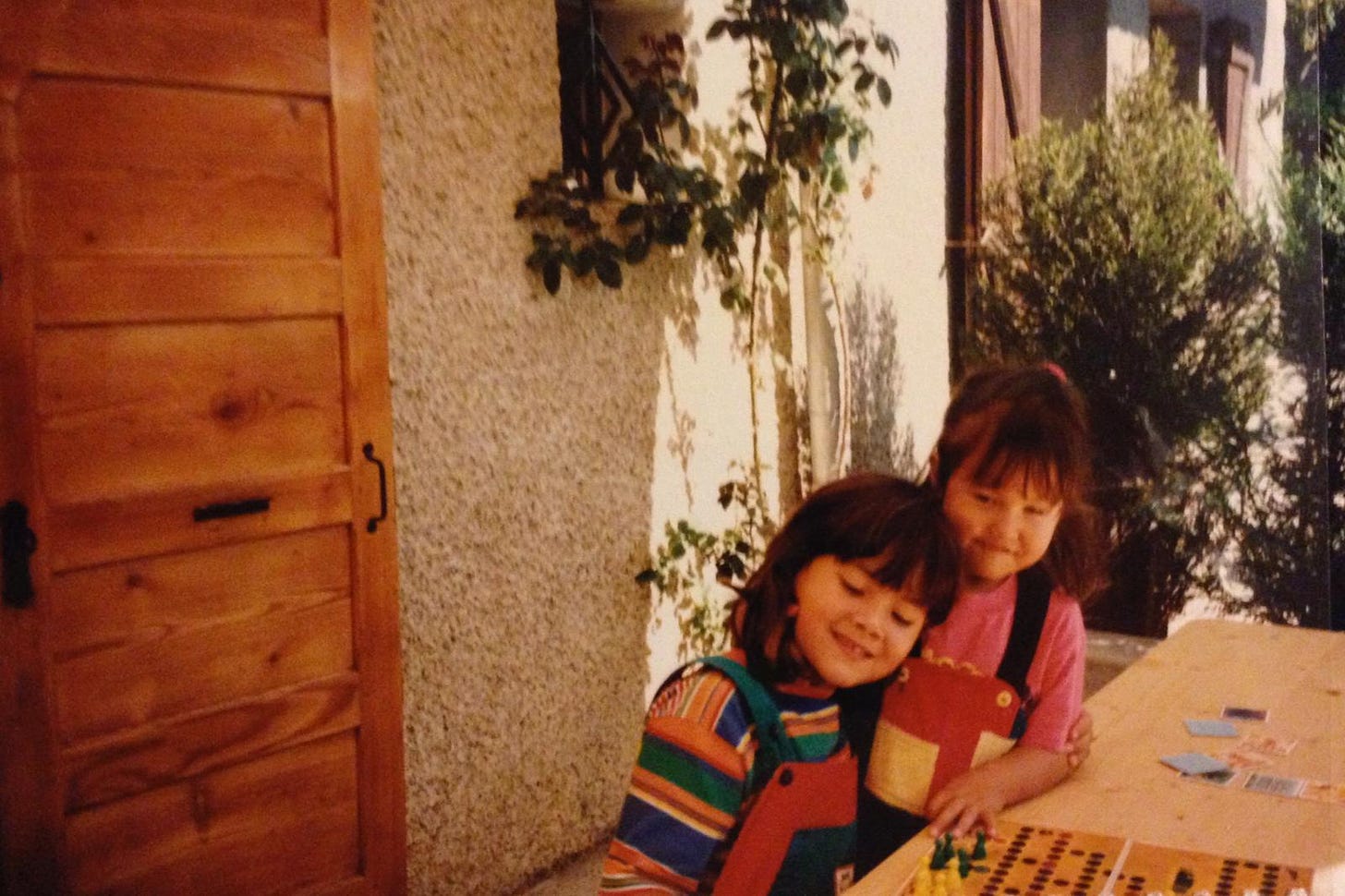

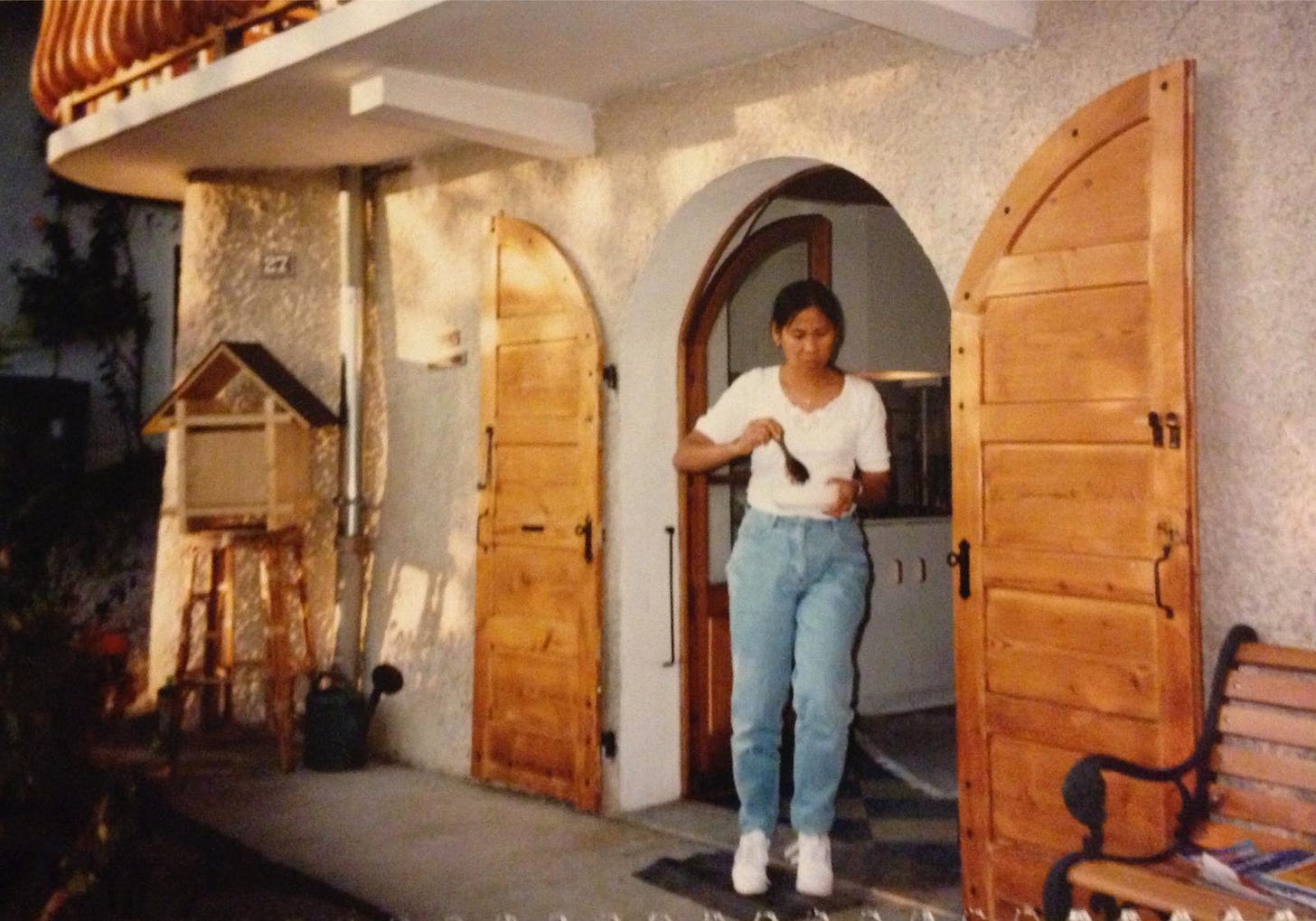

My parents bought and redid the old farmhouse in the ‘90s. Being diplomats, Annecy was the only constant place they could keep their family coming back to. Everywhere else shifted to the tune of an international upbringing: When my Mum was working in Kabul, Daddy brought us to Annecy. When Daddy was in Pakistan, it was Uncle Bernd who brought us there.

Annecy’s walls were thick with personality. As I ran my hands across them they shifted from stone, to cement, to wood, the tapestry of memory unfolding beneath my fingers. This beam: Where Daddy always hit his head. This couch: Where my sister and I read every single Asterix and Obelix comic on the planet. This carpet: Where, during the first New Year’s party I have any recollection of, a visitor wearing 2000s glasses made his bed.

Annecy was the place into which my parents poured their free time and creativity, often stifled by a transient life abroad. Jungles of Ugandan sculptures lined the beamers. Books from countries long-gone colonized Annecy's rickety bookshelves. Remnants from my childhood were crammed in cobwebbed corners: stuffed toys, headless barbies, 300-piece puzzles, Meg Cabot novellas, secret diaries under lock and key, a 3-year old’s rendition of modern art, Polly pocket, bamboo baskets, mini coasters, books in Plautdietsch no one could read, Karamojong stools, blunt, East-African swords.

Cleaning out the house felt like I was losing my childhood – the innocence of those younger days packed into boxes was all-too symbolic. As I emptied the house, our bond seemed to dissipate. It stopped feeling like my house. It felt, in a way, like as I was losing the house, I was losing a part of myself, too.

There was one object in particular that I couldn’t be parted with. Before we had Alexa, we cranked up Annecy’s ‘80s-style radio. Fizzing with static it usually hummed out cathartic French chansons. Except for the station Nostalgie which played the classics on repeat, kindling my future penchant for rock ‘n roll. Daddy wanted to leave the radio in Annecy, but I couldn’t bring myself to let it go. You could say I grew attached to it.

We endow objects with meaning in order to avoid loss. It’s why we clutter our houses, hold onto Grandma’s jewelry, move belongings across continents, and cry when we accidentally forget an object on holiday. We believe these material objects are somehow a part of who we are, a bias called the “endowment effect.” Coined by behavioral economist Richard Thaler, it’s the idea that our possession of something makes it inherently more valuable. When reaching adulthood, artifacts from our childhood are even more endowed, as these objects helped our brains establish memory and a sense of self. Like many biases, our endowments are irrational. To transfer ownership onto the material world stunts our sense of equilibrium when we, inevitably, let them go. I fought to keep Annecy’s radio, and now it sits alone in a dark shed.

Houses, as a whole, can also take on this same veil of importance to those who live in them -- for better or worse. In the same way that we hold on to houses that are imbued with good memories, we sell houses if something tragic or spooky happens within them. In the US, you’re legally required to tell a buyer if someone has died in your house, or if you believe it is haunted. Such knowledge, to a prospective buyer, would undoubtedly shift their perspective on a place. We have a collective understanding that a house isn’t just a concrete space – there is some level of metaphysical energy at work there. It’s like an individual experience of topophilia, the deep love that people have for their material surroundings, as explored by geographer Yi-Fun Tuan. Tuan found that the love people felt for a place was deeply connected to their identity.

Without Annecy being rooted in my childhood, would I have become the person I am today? With Annecy now gone, would I still be the same person? Would my memories and sense of self remain?

It was a place where time stood still. Where Jonny Halliday was still alive. Where Disney movies could only be played on VHS. It was a place that tethered us to each other through the small universe we created there, featuring endless summer holidays, families who stick together, friends substituting gossip for games. In our lives spent moving around, being evacuated, trying on new schools - we always somehow made it back to Annecy.

In The Ecology of Imagination in Childhood, Edith Cobb suggests that children make worlds in which they can discover the self. Annecy was like my fort. It was my equivalent of a treehouse, den, grove, or secret garden. I didn’t have any other play-den, because nothing stood still in those days. Except for Annecy, whose four floors became my special place.

For a kid on the move, a house stands for permanence. Nestled at the foot of a mountain, Annecy felt flushed with force and continuity. When we packed up our belongings, I had to navigate feelings of endings, letting go, giving up, growing up, like selling the house threw a spanner in the works of our familial bliss.

The thing about a place you go back to for short moments in time, like a vacation home, is that you are forced to live every moment like it’s the last. You preserve the memory of each visit like a pocket in time. Annecy’s walls held all those precious moments. Its garden was a temporal oasis of lived experience. Even the parking lot stored my secret damaged bumper while reversing out. The space it took up worked twofold, and the second was conceptual. I navigated Annecy through fantasy as a child and memory as an adult, in order to make sense of a world in flux.

We are masters at taking the places we know and protecting them, imbuing walls with meaning, carpets with memory, roofs and radios with friendships. It’s how we survived a pandemic. It’s why we cherish nostalgia and keep turning it on like an old song from the radio. A house becomes a home through lived experience and love.

I’ll always remember Annecy as my sanctuary. Those short-totting summer days spent walking to and fro Annecy’s big lake. Separated from social media. Charmed by nostalgic pop songs from the ‘60s. Selecting the next princess in her high tower or cottage to watch before bedtime. These memories now mark what’s important to me, reinforced by the totality of the pandemic: Family, love, community, playfulness, and a sense of discovery and wonder.

When I pack up the next home that has sheltered me through a pandemic, I hope, in the same way I did for Annecy, to select the memories that have made me who I am today. We can only hope to use such places as points of reflection – not cement them in time.

Nikole Wintermeier is a Eurasian, female, Blues Rock fan, and writer (not always in that order, but it depends who’s asking). She’s interested in identity politics, and the stories that make us human.

Place Recommends:

Meeting reindeer at the end of the world,

Questioning, who gets to travel to find themselves?

Hitchhiking with bloodworms.

Join us next week for a sensory exploration.

This was such a beautiful article. It resonated with me a ton. I could almost place myself in your memory as you described it, seeing the years fly by. In the end, it's the accumulation of places, things, people, memory, and time spent that creates our ground beneath us, rather than just the place alone.